A Deceptively Simple Need

2025—ongoing

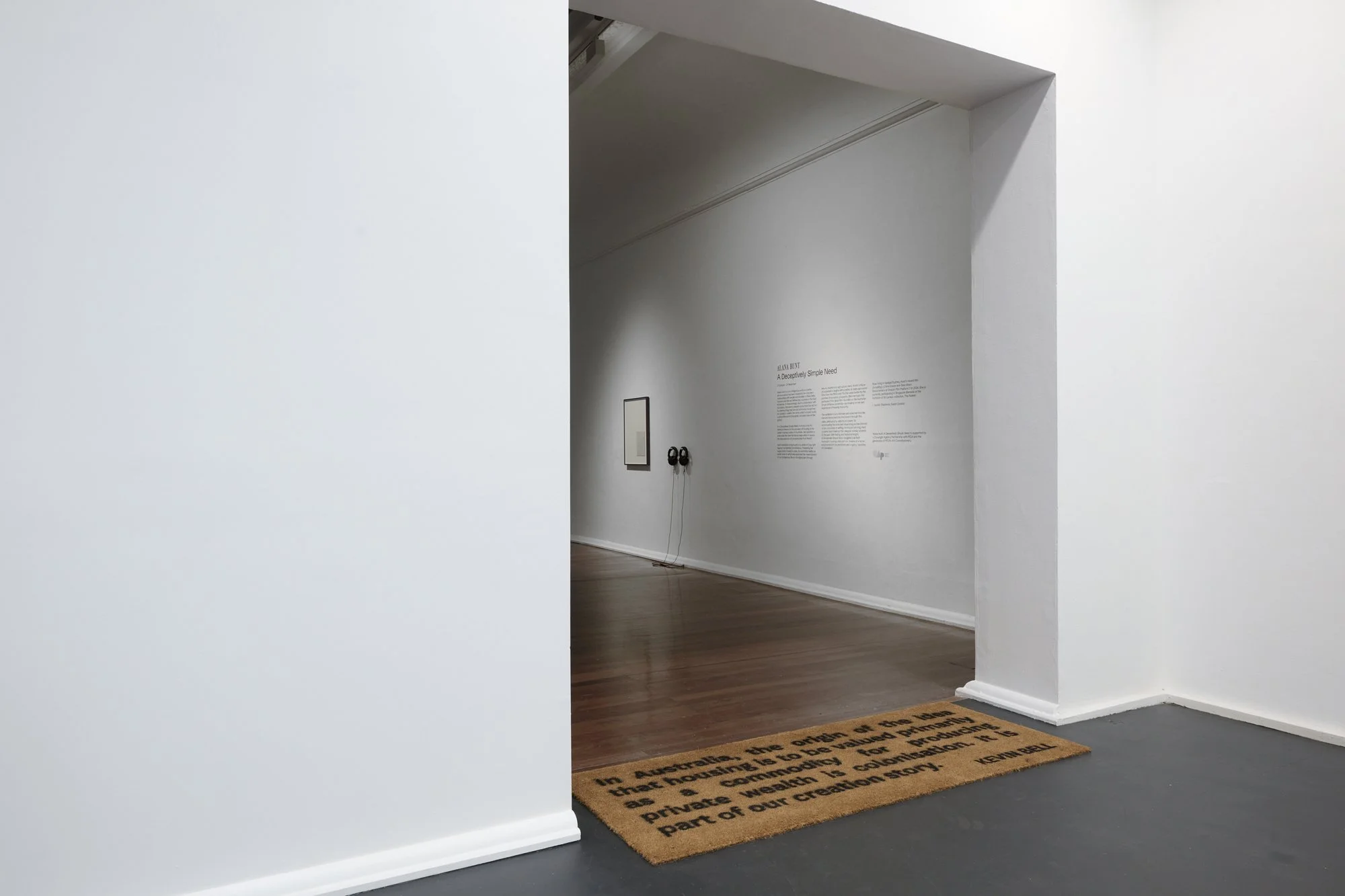

A Deceptively Simple Need is grounded in the tension between the genuine need for home that everyone has, and the inherent violence of that need on unceded land. Within the settler-colonial structures of Australia, at the heart of every home lies the displacement of First Nations people from theirs.

The first iteration of this body of work opened at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art (17 October - 21 December 2025), in a solo exhibition supported by the Copyright Agency’s Partnerships Commission and curated by Jasmin Stevens. Central to this exhibition are my own experience of housing insecurity, reflections on the current housing crisis, and a critical re-mixing of state-sponsored films made in Western Australia during the 1960s and 70s, when the State celebrated its one millionth colonial citizen.

The works span intimate and collective histories that are transposed into the present through film, video, photography, objects and paper. By accentuating materialities intrinsic to the processes of writing, filming and printing, this work disrupts fixed timelines that relegate colonial violence to the past. With feeling and historical insight, A Deceptively Simple Need is a self-reflexive account of the weaponisation of home within settler-colonial structures and the crisis that has ensued.

Below is detailed documentation of the exhibition at PICA, from entry to exit.

Further reading:

Got Any Land? exhibition essay by Lauren Carrol Harris

The tensions inherent in Australia's housing crisis laid bare at Perth gallery by Emma Wynne for ABC News, 2 November 2025

installation images by Rebecca Mansell

Australai’s Desterney, 2025

Colour HD video with sound 33m28s (camera: Ben Lindberg)

Graphite on A4 paper (80 x 60cm framed)

Reminiscent of lines written during a school detention, the phrases drawn from the WA government’s commissioned films are absurd, almost sci-fi, but also blunt with the kind of blind confidence characteristic of colonial life.

Like the hand-written word, the inner voice of the child is discreet—fuelled with the charm of innocence and error; it captivates, and then distrubs.

Alana Hunt, artist

In these works, the titles of the Western Australian Government films at the centre of Hunt’s exhibition are recorded in different formats—spoken word, pencil inscription and video. This task of translating the titles from the panoramic to the personal is delegated to a child. In ways reminiscent of a school detention, they are reproduced as a dense repetitive text, as a recitation and as a framed testamur.

Titles such as ‘Salt of the Sun’ and ‘Trade Routes of the Future’ have an indexical relationship to the ideology of state development that is celebrated in the original films. They act as signs pointing to settler-colonial thinking that links notions of individual and social progress to an expansionist ethos of industry and property ownership. Hunt contends that despite the innocence of the child—embodied in the tenor of their voice and the deliberate nature of their handwriting—the violence carried by the grandiose language of the titles seeps into all the institutions of our lives.

Jasmin Stephens, curator

excerpt from Australai’s Desterney, full duration 33m28s

A riot of colour and Rubble, 2025

acrylic, LED and aluminium lightboxes / 3 x light boxes: 100 x 150 x 20 cm (each) / 6 images: 99 x 149 cm (each)

Pink Western Australian “wildflowers” provide a soft ground of arrival, only to be undercut by the ease at which non-indigenous people like to consume native flora in the absence of Indigenous people — a common thread of colonialism from Kununurra to Kashmir, Port Hedland to Palestine. On the flip side of these light boxes is the demolition of a home—simply titled “Rubble”. It is a blunt picture of what settler colonialism does—a process of destruction and replacement. Home becomes a weapon used to acquire stolen goods that generations are profiting from.

Alana Hunt, artist

Hunt’s light box works juxtapose Western Australian wildflowers in bloom with the aftermath of demolition. One of their titles, A riot of colour, suffuses the exhibition, also appearing in the adjacent video works, Displacement and Replacement and A Community is Formed. Both the floral imagery taken from the archival films and Hunt’s photographs of a suburban lot have an oblique relationship to the crisp aesthetic of the world of advertising.

Indigenous writer Tristen Harwood has previously observed the forensic quality in Hunt’s photography. He has written, ‘Alana’s lens seems to surveil the people and acts in the places she

photographs, as though she were documenting the landscape—the colonial mythscape—as a crime scene’. On these terms, as Hunt documents a home reduced to rubble, she uncovers a ‘mythology’ that is accorded national significance but is in fact compelled by a view of housing as an industry for the creation of private wealth. Arising from this, Hunt’s combining of sets of discordant images is intended to link the embracing of wildflowers by non-Indigenous society to a simultaneous blindness to the workings of colonisation.

Jasmin Stephens, curator

Displacement and Replacement, 2025

colour HD video with sound 4:3 / 73m28s

A Community is Formed, 2025

black and white video 4:3 / 15m00s

In this accumulative remix of 12 films in 12 chapters phrases from the film’s original narration have been pulled on to highlight the ideological and material violence of the colonial project — unfolding through the banality of things like roads, railways, mines, agriculture, farming and the weaponisation of things we commonly hold dear, like “community” and “home”.

Alana Hunt, artist

During the 1960s and 70s, the Western Australian Government commissioned a series of films that not only recorded economic milestones but propagated an image of the State as a land of abundance. These films are now held by the State Library of Western Australia. Produced by Bryan Lobascher (1926-2022), their declarative tone conveyed an unwavering confidence in the destiny of Western Australia in which a rhetoric of housing, community and prosperity was central to the State’s expanding economy.

In these 12 films, the repetition of scenes that overlay human figure, infrastructure and landscape builds a cumulative picture of colonialism. The films convey a totalising world view that binds labour, dreams and materials together. To Hunt, this world view is accompanied by a process of displacement and replacement that is ‘persistent and unending’.

For this exhibition, Hunt reconfigures Lobascher’s archival films (now out of copyright) through conceptual strategies that slow this momentum. She extracts and interleaves phrases so that they no longer bolster convivial narratives of belonging, but disclose a more haunting brutality. Prising the linguistic and visual tropes of development apart, Hunt inserts a commentary that shifts our reception of the films from the recent past to the present. This arrangement of texts and images reinforces how the colonising values of state development are cloaked in bureaucratic language and in the familiar rhythms of daily life.

Jasmin Stephens, curator

excerpt (chapter 2 of 12) from Displacement and Replacement (2025) total duration 73m28s

excerpt from A Community is Formed (2025) total duration 15m00s

When We Win Lotto. 2025

40 polaroid photographs mounted on wood, shelf / 9 x 11 x 0.5cm each

Nice Car. Can’t sleep in it. 2025

64 polaroid photographs mounted on wood, shelf / 9 x 11 x 0.5cm each

Running like a thread or lure from the main gallery into the smaller back galleries—moving from the historical into the present, shifting between the societal and the personal—are these 104 Polaroid photographs.

Alana Hunt, artist

Hunt’s polaroids, numbering 40 (Hunt’s age) in the case of the houses, and 64 (her mother’s age) in the case of the sports cars, are arranged in the gallery as a chronology or a strip of time. They are inspired by her mother’s quips about flash cars and the prospect of owning a home.

As Hunt remarks in the photobook of these works:

When We Win Lotto.

‘For as long as I can remember my mother and I have looked at houses—houses that are quaint and humble, and houses that are excessive and bold—and she has said to me, when we win lotto. I am now 40 years old. We are yet to win lotto. And we are yet to own a house. I catch myself looking at houses and saying the same phrase to my son.’

Nice Car. Can’t sleep in it.

‘For as long as I can remember my mother’s core criteria for a good car is one that you can sleep in. Nice car. Can’t sleep in it. She says this with cheek—a way of dissing fancy small cars and offering a counter ode to a spirit of adventure and agility shaped by road trips and camping. But there is an undercurrent to this too, one fuelled by a lifetime of persistent housing precarity.

She is now 64 years old. Women over the age of 55 are the fastest growing group to experience homelessness in Australia.’

Convenient and portable, the polaroid exemplifies Hunt’s attraction to humble materials and processes, ensuring that art can be made with whatever is at hand. Car journeys and chance encounters are the conditions for the creation of these works within a transient life.

Jasmin Stephens, curator

Shelving by Graphic Art Mount, Sydney.

104 polaroid images on an 8m long accordion fold book. An exhibition in a box that folds into the palm of your hand. Purchase a copy here.

Bricks and Mortar, 2025

Super 8mm film transferred to colour video, 4:3 / 5m44s

Beach. 2025

Super 8mm film transferred to colour video, 4:3 / 8m40s

Both Beach and Bricks and Mortar appear as a place of transition in the exhibition from one experience or tenor or time into another.

The beach as the point of colonial arrival (and possible departure). The site of rising oceans caused by industrialisation, and this continent’s most expensive real estate. The brick as the most concrete manifestation of colonialism — one brick, one house, one settler’s life at a time. The use of reversal raises the possibility (and impossibility) of undoing all of this.

(I always chuckle that the dude in Beach picks the towel up for himself, a subtle record of male entitlement caught on film.)

Alana Hunt, artist

In this gallery, generic images of work and leisure convey the industry, the environs and the privilege of a settler-colonial life. Brick by brick, house by house and beach by beach, an edifice or pattern of colonial life emerges. Hunt’s use of reversal in these scenes, however, disrupts their easy consumption; familiar scenarios stall—only to be caught in a cycle of making and unmaking and of arrival and departure. This forwards and backwards manoeuvre points to a malfunction, a reminder that the process of colonisation cannot be undone coupled with the simultaneous proposition: what if it was?

Given this, the beach—the point of colonial arrival and the site of the country’s most desirable real estate, which drives the material aspirations of so many—contributes to an ever more fractured economic and social divide. As jurist and housing advocate Kevin Bell argues, the right to housing should be ‘enshrined in law’. While housing functions as a system propelled by financial speculation, homes will be treated as commodities rather than as the foundation of human dignity.

Jasmin Stephens, curator

Special thanks to Maile Bowen, Adrian Fini, Mitch Hill, Karina Hillier and Red Rock Brickworks.

excerpt of Bricks and Mortar, total duration 5m44s

excerpt of Beach, total duration 8m40s

the deceptively simple need for a home (on other people’s land), 2025

Super 8mm film transferred to colour video, 4:3 / 21m26s

This work recounts an experience of a childhood spent in rented accommodation. While not uncommon, this account is distinctive for the manner in which it sets out to disrupt the entitlement to housing enshrined in settler-colonial life. It does this by invoking the child’s interpersonal and class circumstances.

Composed of 14 vignettes or episodes—one for each of the houses that the child lived in until leaving school—the work has an underlying feeling of vulnerability despite its humour. To this end, the child is introduced as ‘on the edges’, observing the mother who often rearranges the furniture as ‘though the rearrangement would solve their problems’.

A cumulative unease is created in the work by a fragmentary anecdotal approach that digresses from the steady gaze of the camera. These anecdotes are revealing of historical forces beyond the film’s domestic spaces and suburban terrain. For lodged in memories of make-believe, teenage camaraderie and maturing experiences across a widening geographic range are traces of the locality’s First Nations people and the process of their attempted erasure. As this narrative betrays, the need for a home is ‘deceptively simple’; on one hand, it is instinctive and universal and, on the other, it bears the injustice of non-Indigenous life on stolen land.

Jasmin Stephens, curator

…in the video work the deceptively simple need for a home (on other peoples’ land), the woman reciting her wobbly childhood rental history needs care. The video takes on a mythical quality by refusing to name its anyplace suburban locations. Against the sound of eggs frying, the girl’s itinerant timeline is marked by points of Indigenous erasure: a reference to Truganini in her school curriculum, an encounter with an Aboriginal midden, displacement for the construction of a sports stadium. While the girl’s life is complicit in the colonial project, she is suffering from precarity too, wrote a friend of Alana’s in an email upon seeing the video, in her life with a single mother in insecure work. I love this generous reading, because it shows the beautiful opportunity for solidarity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people on the question of land—if we are honest about repatriation and what cannot be undone. It’s this very desire for solidarity that has seen some private landholders begin to hand back entire valleys and paddocks. In 2019, an elderly farming couple, the Teniswoods, returned half their 220 hectare property in Little Swanport to the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania—a healing, humble action far ahead of government policy.

excerpt from the deceptively simple need for a home (on other people’s land) total duration 21m28s

To the Owner (of multiple properties), 2025-ongoing

1000 x A1 letters folded into 1000 x A4 envelopes for distribution

offset print on high bulk paper

This work is a seed (in the form of a letter). Exactly what it grows into and how and where, is yet to be seen.

Suggestions for people or places where this letter could be sent are most welcome: skyabovetheclouds (at) hotmail (dot) com

________

To the Owner (or multiple properties),

This might seem like an absurd proposition, but in many ways it is the most realistic path to stable housing that lies before me.

I am an artist and writer. I am seeking a patron to provide me with a house to live in free of charge for a decade.

There are approximately one million empty houses in Australia, representing about 10.1% of the nation’s private dwellings, according to 2021 Census data.

Do you own one? I will turn your empty house into a home.

You will in turn play a central role in an evolving art work of profound social importance, while supporting an artist’s career.

All the work I produce over the course of that decade long lease will be credited:

This work has been supported by (insert your name here).

I look forward to discussing this possibility with you.

Respectfully,

Alana Hunt

________

One million houses stand empty in Australia, despite the universal need for secure tenure and an adequate standard of living. Alana recently sat down at her desk to write a letter seeking a patron, who would ideally be an owner of multiple spare houses offering a rent-free lease for ten years in return for credit in all Alana’s work. “This might seem like an absurd proposition, but in many ways it is the most realistic path to stable housing that lies before me,” wrote Alana, balancing satire and seriousness. She has printed 1000 A1 copies of this letter, packaged them into envelopes and stamped the front with the words “To the Owner (of multiple properties)” in red ink. She plans on letter-dropping them to the most expensive postcodes in Sydney and Perth, and wherever else the work may lead.

Such are the enduring inequalities for a system that sees shelter as an asset.

“In the 1990s, when stories about land rights and the Wik decision were on the nightly news, racists would taunt and threaten that Indigenous people would ‘come for our homes’. ‘Why can’t they come for our homes? And what would happen if they did?’ Alana asked me in her studio. ‘I would like to have a home. And that’s the tension.’ She’s making a case for the radical beauty of shared personal responsibility for colonial injustice. So: got any land?”

Got Any Land?! by Lauren Carroll Harris

further reading

Got Any Land? essay by Lauren Carrol Harris

The tensions inherent in Australia's housing crisis laid bare at Perth gallery by Emma Wynne for ABC News, 2 November 2025